Echoes of Assassinations: Visiting Gyeonggyojang on a Historic Morning

On the morning of July 14, my social media feed was flooded with photos of the shooting at a Donald Trump rally. The image was undeniably powerful: under the Stars and Stripes, a 78-year-old man with a bloodied face pumped his fist, calling for Americans to “FIGHT”. Whether one views him as a master of political theater or a resilient leader, his composure in that moment was remarkable. The photographer’s instinct—finding the angle and capturing the shot amidst the chaos—was equally professional.

Political assassinations are not uncommon in democratic nations. Lincoln, Kennedy, McKinley, and Garfield all died at the hands of assassins. Japan and South Korea have also seen their share of leaders meeting violent ends. The stability of a nation following such an event is often a litmus test for the health of its political system. In an autocracy, the death of a leader is almost always a catastrophe for both the state and the individual.

By a striking coincidence, on that very morning in Seoul, I was headed to Gyeonggyojang, the site where one of Korea’s greatest leaders, Kim Koo, was assassinated.

Kim Koo: The Father of the Nation

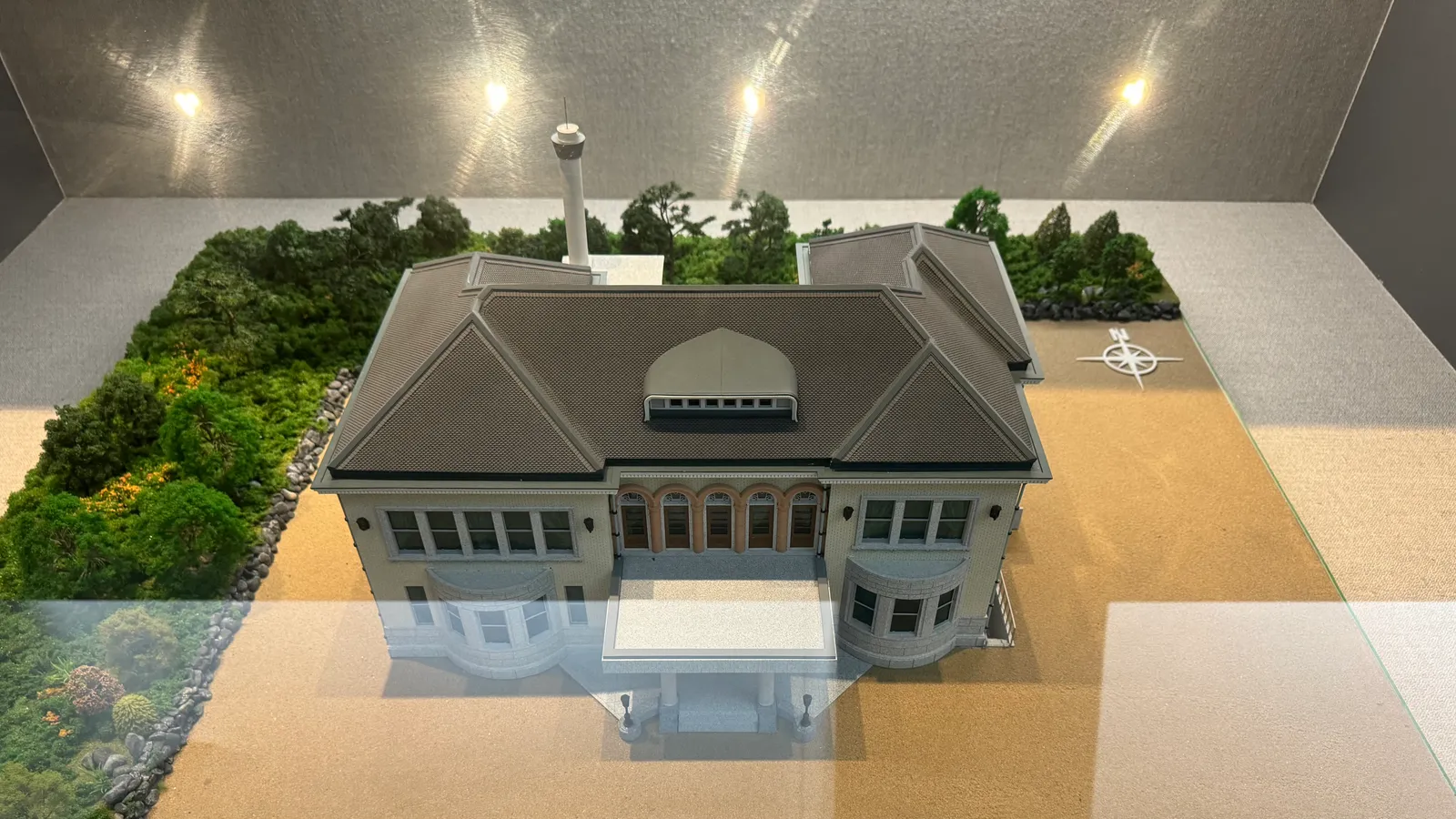

Tucked away within the grounds of the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital in western Seoul is a historic building known as Gyeonggyojang. Once the headquarters of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea, it served as the home and eventually the place of death for Kim Koo.

The exhibition at Gyeonggyojang is remarkably accessible, with all major displays presented in Korean, English, and Chinese. This trilingual approach reflects the deep historical ties between the Korean independence movement and China. The Provisional Government was essentially a government-in-exile, founded in Shanghai in 1919 with significant support from the Chinese Nationalist government.

Kim Koo, often referred by his pen name Baekbeom, was the President of the Provisional Government and is widely revered as the “Father of the Nation” in South Korea. While Syngman Rhee was initially considered the founding father, Kim Koo’s legacy was formally elevated after the 1960 April Revolution.

Two Chilling Reminders

Within Gyeonggyojang, two exhibits left a lasting impression:

- The Blood-Stained Clothes: In the basement exhibition hall (which was once a boiler room), you can see the clothes Kim Koo was wearing when he was killed. Over the decades, the bloodstains have darkened into a deep, somber brown.

- The Bullet Holes: On the second floor, in the room where Kim Koo lived and worked, two bullet holes remain in the window. On June 26, 1949, Kim Koo was assassinated by Ahn Doo-hee, a right-wing army lieutenant. Four bullets were fired: one pierced his philtrum, another his neck, and two more his chest and abdomen. He died on the spot.

Some believe the assassination was orchestrated by Syngman Rhee. Ahn Doo-hee met a grim end years later, dying at the hands of one of Kim Koo’s supporters. Kim Koo had dedicated his life to the peaceful unification of the Korean people; it’s a tragic irony that after his death, the right-wing took power and the peninsula was permanently divided.

A Symbol of Korean Democracy

Today, Gyeonggyojang is owned by the Samsung Group and integrated into the hospital complex. For decades, the historic building was used simply as part of the hospital’s entrance. It wasn’t until 2013 that its historical significance was fully recognized, and the Seoul city government restored the rooms to their original state.

The struggle to preserve Gyeonggyojang mirrors Korea’s broader journey toward democracy. For thirty years, restoration efforts were blocked by corporate interests, but the persistence of activists eventually won out. Today, the site stands as a testament to a people who have fought bravely—from Japanese colonial rule to military dictatorships—to establish one of the most vibrant democracies in East Asia.

For those interested in this period of history beyond textbooks, Korean cinema has produced some exceptional works. Films like 12.12: The Day, A Taxi Driver, The Attorney, and 1987: When the Day Comes provide a visceral look at the human cost of Korea’s democratic struggle. Together, they form a heroic and often heartbreaking history of a nation’s birth and rebirth.

Founder of Yonder Song, documenting slow travel, local food culture, and everyday human storie.

Leave a comment

0